1947-1954:

There is little reason to doubt most of Ann Cornelisen’s account of Gianna’s early experiences in Italy although it seems likely that Gianna would have made contact with Ernest rather earlier than suggested in ‘Where It All Began’. By the time she arrived, Ernest had been working in Italy for over 2 years and for the last 18 months had been based in Ortona. He was probably the most experienced social worker in the region. It would seem only natural that the new arrival would look to the old hand for help and advice.

Gianna claimed that she was inadequately prepared by the SCF for her work in Italy. In a letter of May 13 1969 Ann Cornelisen wrote to her publisher “ (In 1947)…the Fund…sent Gianna off into the blue without funds, transportation or even a clear idea of what she was to do.” The Fund arranged for her to lodge in Lanciano with the head of the Women’s Catholic Action. It was a bad decision. Her hostess, known as La Pontificia, was politically biased, favouring right wing Catholics in her distribution of relief aid. Gianna held firmly to the belief that aid should be given to the most deserving no matter what their political or religious beliefs might be. As a lodger with La Pontificia, Gianna was compromised. Also, Lanciano was unsuitable as a base. It is 10 miles inland and there was no railway link. Gianna’s supplies of food and clothing for her proposed nurseries and feeding centres would arrive by rail at Ortona on the coast and then have to be transported by road to Lanciano.

There were more transport problems: Gianna’s remit was to begin establishing nurseries in the villages along the Sangro valley. She had no transport of her own and public transport was either unreliable or non-existent. She found herself hitching lifts and tramping along mountain paths to reach the isolated villages. Ernest was still working with the CASAS house building teams and had access to transport. It was inevitable that they were thrown together sooner rather than later.

Gianna spent the Christmas of 1947 with the Salesian Brothers at the orphanage in Ortona and probably sometime in 1948 she moved from Lanciano and began living at the house occupied by Ernest and the other aid workers in Ortona. According to Ann Cornelisen, Gianna’s mother came from England to vet the arrangement, at which time she noted and approved of the growing relationship between her only daughter and Ernest.

Gianna’s supplies began arriving more regularly but she needed help with the lifting and hauling. A young Italian had attached himself to Ernest. He was called Sorino. He was eager to work, knew everybody in Ortona, was quick witted, strong and ingenious. He could build an engine from bartered or stolen parts and could turn his hand to any physical labour. ‘(Sorino) worshipped Ernest, would protect anything or anyone that was his, which he quickly perceived as including Gianna. She had hired a navvy and got, instead, a man of all work and a bodyguard.’ (Ann Cornelisen). Sorino remained with Gianna throughout her career with the SCF. Sometime during this period Ida joined Gianna’s staff as housekeeper/cook. Despite all the comings and goings of friends and personnel over the next 20 years, Sorino and Ida were to remain with Gianna in Ortona at the centre of the SCF operation.

Gianna’s work expanded as she trained teachers in modern child welfare techniques, established nurseries in the remote mountain villages and managed child sponsorship schemes. In her book AC writes that by the late 40s Ernest’s work was ‘winding down’ and he was devoting himself to supporting Gianna’s work. Contemporary accounts suggest otherwise.

Louise Woods reported to the American Friends Service Committee: ‘We have done a significant job in Italy ….Ernest Thompson visits family after family in the Abruzzi and works out with them some solution to their countless problems.’

William Huntington, another AFSC official wrote on Feb 16 1949: ‘Ernest’s services extend to the welfare of the communities of the district beyond the particular groups of CASAS houses. He works on an area around Ortona extending from Palena to the North to the upper reaches of the Aventino valley. His jeep, owned by us is, of extreme value to his work and enables him to be a great deal more effective than the average CASAS worker.’

‘Ernest Thompson had a little money from AFSC at his disposal which was used to provide bedding, medical care and other emergency needs to some of the most desperately poor people of the area. He also received artificial glass, for window panes, some shipments of textiles to provide clothing for infants and adults and 4300 packets of garden seeds, each sufficient to plant a garden for a family of 5.’ (Louise Wood).

Ernest and Gianna’s work overlapped and they worked as a team. In a 1949 report to the American Friends HQ in Philadelphia, Ernest gives an idea of how they operated: ‘There are to be no charitable handouts. When there is work to be done at the Villagio (orphanage), hospital or old people’s home for example, they tell us. If somebody wants a pair of shoes they work for them. The hospital needs nightgowns, the old people’s home needs some underwear: we have the material and the women have the time, so the two get together and the pay is the pair of shoes or whatever they need. For the men there are opportunities to make a pathway or a chicken coop, work always for the community and which would not get done otherwise. In payment for this they might ask for a coat for the wife or a dress for the child.’ This method remained a cornerstone of Gianna’s work throughout her time in Italy.

Ernest and Gianna’s personal relationship developed slowly. Ann Cornelisen describes how two ‘relentlessly idealistic people discussed, argued and theorized as a relief from the insistent, gritty problems of how to feed children, how to build houses for them, how to force a mayor to pipe water or consider an even more revolutionary installation, sewers. They enjoyed their chiding, teasing and tussles with the Perfect World and soon, long before they would admit it, there was something less arcane between them. It was unplanned, unprofessional and unseemly: they were falling in love.

They decided to get married. After overcoming many bureaucratic obstacles they finally did so in Rome in September 1950. AC does not relate who else was present at the wedding although she does say that they spent their honeymoon escorting an SCF official on an inspection tour of Southern Italy.

They moved into a small peasant house on the Southern outskirts of Ortona and it was there, on a triangle of land once occupied by a gun battery, that the council gave land for Gianna to build a nursery which would act as a model for other nurseries that she would build. Prefabricated units were donated and Ernest and Sorino ‘set up as small scale contractors.’ Possibly through Ernest’s influence, the SCF was given the old UNRRA auto park as a storage depot for the clothing and supplies sent for distribution from northern Europe.

Ernest remained working for UNRRA- CASAS. In Ortona, he and Gianna established a club for young people with money from the AFSC. In 1952 Warren Staebler, a visiting AFSC official wrote to Ernest: ‘I certainly was impressed by what I saw of the club last week. You and Gianna have made an irresistibly attractive centre building and have started an enthusiastic and responsive club. I congratulate you both on what you have done. The problem as you say is how to develop a club into a centre. If the centre is to be really a community centre it must touch more parts of the community, more parts of aspects of its life. And to do this it must be a pretty full programme of adult education.’

In the spring of 1952 Ernest began to feel unwell. There was nothing specific but his appetite came and went and he was sleeping badly. He decided to go abroad for treatment at the end of September.

Ernest and Gianna’s second wedding anniversary fell in early September 1952. It was a hot afternoon and Ernest and Sorino decided to take a group of youth club boys for a swim at the beach just below where he and Gianna lived and where the nursery was being built. They did this regularly in summer and Ernest would amuse the boys by diving underwater and dunking one of them into the sea. The game continued until, on one occasion, Ernest failed to appear.

‘For two nights and a day Gianna sat by a window looking at the sea, while Sorino, his friends and the local fishing fleet trawled for Ernest’s body. At dawn of the second day, they found him.’ (AC)

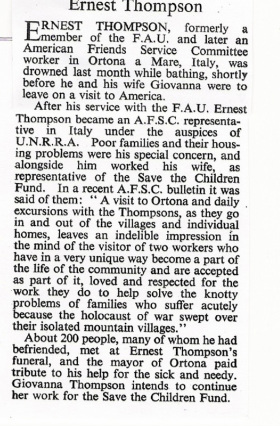

Over 200 people attended his funeral in Ortona. The following obituary appeared in The Friend, the Quaker newspaper.

There is little reason to doubt most of Ann Cornelisen’s account of Gianna’s early experiences in Italy although it seems likely that Gianna would have made contact with Ernest rather earlier than suggested in ‘Where It All Began’. By the time she arrived, Ernest had been working in Italy for over 2 years and for the last 18 months had been based in Ortona. He was probably the most experienced social worker in the region. It would seem only natural that the new arrival would look to the old hand for help and advice.

Gianna claimed that she was inadequately prepared by the SCF for her work in Italy. In a letter of May 13 1969 Ann Cornelisen wrote to her publisher “ (In 1947)…the Fund…sent Gianna off into the blue without funds, transportation or even a clear idea of what she was to do.” The Fund arranged for her to lodge in Lanciano with the head of the Women’s Catholic Action. It was a bad decision. Her hostess, known as La Pontificia, was politically biased, favouring right wing Catholics in her distribution of relief aid. Gianna held firmly to the belief that aid should be given to the most deserving no matter what their political or religious beliefs might be. As a lodger with La Pontificia, Gianna was compromised. Also, Lanciano was unsuitable as a base. It is 10 miles inland and there was no railway link. Gianna’s supplies of food and clothing for her proposed nurseries and feeding centres would arrive by rail at Ortona on the coast and then have to be transported by road to Lanciano.

There were more transport problems: Gianna’s remit was to begin establishing nurseries in the villages along the Sangro valley. She had no transport of her own and public transport was either unreliable or non-existent. She found herself hitching lifts and tramping along mountain paths to reach the isolated villages. Ernest was still working with the CASAS house building teams and had access to transport. It was inevitable that they were thrown together sooner rather than later.

Gianna spent the Christmas of 1947 with the Salesian Brothers at the orphanage in Ortona and probably sometime in 1948 she moved from Lanciano and began living at the house occupied by Ernest and the other aid workers in Ortona. According to Ann Cornelisen, Gianna’s mother came from England to vet the arrangement, at which time she noted and approved of the growing relationship between her only daughter and Ernest.

Gianna’s supplies began arriving more regularly but she needed help with the lifting and hauling. A young Italian had attached himself to Ernest. He was called Sorino. He was eager to work, knew everybody in Ortona, was quick witted, strong and ingenious. He could build an engine from bartered or stolen parts and could turn his hand to any physical labour. ‘(Sorino) worshipped Ernest, would protect anything or anyone that was his, which he quickly perceived as including Gianna. She had hired a navvy and got, instead, a man of all work and a bodyguard.’ (Ann Cornelisen). Sorino remained with Gianna throughout her career with the SCF. Sometime during this period Ida joined Gianna’s staff as housekeeper/cook. Despite all the comings and goings of friends and personnel over the next 20 years, Sorino and Ida were to remain with Gianna in Ortona at the centre of the SCF operation.

Gianna’s work expanded as she trained teachers in modern child welfare techniques, established nurseries in the remote mountain villages and managed child sponsorship schemes. In her book AC writes that by the late 40s Ernest’s work was ‘winding down’ and he was devoting himself to supporting Gianna’s work. Contemporary accounts suggest otherwise.

Louise Woods reported to the American Friends Service Committee: ‘We have done a significant job in Italy ….Ernest Thompson visits family after family in the Abruzzi and works out with them some solution to their countless problems.’

William Huntington, another AFSC official wrote on Feb 16 1949: ‘Ernest’s services extend to the welfare of the communities of the district beyond the particular groups of CASAS houses. He works on an area around Ortona extending from Palena to the North to the upper reaches of the Aventino valley. His jeep, owned by us is, of extreme value to his work and enables him to be a great deal more effective than the average CASAS worker.’

‘Ernest Thompson had a little money from AFSC at his disposal which was used to provide bedding, medical care and other emergency needs to some of the most desperately poor people of the area. He also received artificial glass, for window panes, some shipments of textiles to provide clothing for infants and adults and 4300 packets of garden seeds, each sufficient to plant a garden for a family of 5.’ (Louise Wood).

Ernest and Gianna’s work overlapped and they worked as a team. In a 1949 report to the American Friends HQ in Philadelphia, Ernest gives an idea of how they operated: ‘There are to be no charitable handouts. When there is work to be done at the Villagio (orphanage), hospital or old people’s home for example, they tell us. If somebody wants a pair of shoes they work for them. The hospital needs nightgowns, the old people’s home needs some underwear: we have the material and the women have the time, so the two get together and the pay is the pair of shoes or whatever they need. For the men there are opportunities to make a pathway or a chicken coop, work always for the community and which would not get done otherwise. In payment for this they might ask for a coat for the wife or a dress for the child.’ This method remained a cornerstone of Gianna’s work throughout her time in Italy.

Ernest and Gianna’s personal relationship developed slowly. Ann Cornelisen describes how two ‘relentlessly idealistic people discussed, argued and theorized as a relief from the insistent, gritty problems of how to feed children, how to build houses for them, how to force a mayor to pipe water or consider an even more revolutionary installation, sewers. They enjoyed their chiding, teasing and tussles with the Perfect World and soon, long before they would admit it, there was something less arcane between them. It was unplanned, unprofessional and unseemly: they were falling in love.

They decided to get married. After overcoming many bureaucratic obstacles they finally did so in Rome in September 1950. AC does not relate who else was present at the wedding although she does say that they spent their honeymoon escorting an SCF official on an inspection tour of Southern Italy.

They moved into a small peasant house on the Southern outskirts of Ortona and it was there, on a triangle of land once occupied by a gun battery, that the council gave land for Gianna to build a nursery which would act as a model for other nurseries that she would build. Prefabricated units were donated and Ernest and Sorino ‘set up as small scale contractors.’ Possibly through Ernest’s influence, the SCF was given the old UNRRA auto park as a storage depot for the clothing and supplies sent for distribution from northern Europe.

Ernest remained working for UNRRA- CASAS. In Ortona, he and Gianna established a club for young people with money from the AFSC. In 1952 Warren Staebler, a visiting AFSC official wrote to Ernest: ‘I certainly was impressed by what I saw of the club last week. You and Gianna have made an irresistibly attractive centre building and have started an enthusiastic and responsive club. I congratulate you both on what you have done. The problem as you say is how to develop a club into a centre. If the centre is to be really a community centre it must touch more parts of the community, more parts of aspects of its life. And to do this it must be a pretty full programme of adult education.’

In the spring of 1952 Ernest began to feel unwell. There was nothing specific but his appetite came and went and he was sleeping badly. He decided to go abroad for treatment at the end of September.

Ernest and Gianna’s second wedding anniversary fell in early September 1952. It was a hot afternoon and Ernest and Sorino decided to take a group of youth club boys for a swim at the beach just below where he and Gianna lived and where the nursery was being built. They did this regularly in summer and Ernest would amuse the boys by diving underwater and dunking one of them into the sea. The game continued until, on one occasion, Ernest failed to appear.

‘For two nights and a day Gianna sat by a window looking at the sea, while Sorino, his friends and the local fishing fleet trawled for Ernest’s body. At dawn of the second day, they found him.’ (AC)

Over 200 people attended his funeral in Ortona. The following obituary appeared in The Friend, the Quaker newspaper.

Gianna ordered a simple funeral: a plain casket with Ernest’s body wrapped in a plain sheet. Writing over 30 years later, AC describes how conservative elements in Ortona thought that this simplicity reflected a lack of respect for the dead and that Sorino believed that it failed to honour the man to whom he owed so much. Secretly, he arranged with Ida to smuggle one of Ernest’s suits out of the house and ordered the undertaker to dress the corpse. Furthermore, out of his own pocket he paid to have the coffin lined with lead: all this done without Gianna’s knowledge. The full truth of the story will probably never be known, but it reveals the extraordinary bond between the two men and why, many years later, I was warned not to ask impertinent questions.

Despite Ernest’s death ‘The Work’ continued. (Gianna always made a distinction between ‘The Work’ which related to improving the conditions of the people and the administrative and social tasks she was obliged to perform by her superiors in London.) The Ortona nursery was fully operational and she established more nurseries in the villages of the Sangro. Warren Staebler and Louise Wood, the AFSC representative in Rome, provided emotional support and Ida and Sorino remained as loyal as ever. Guests from abroad were now beginning to arrive: either SCF officials on visits of inspection or important donors from branches in Europe, Canada or Australia. All had to be entertained, taken on long trips to visit projects in remote villages and given lectures on the nature of ‘The Work’ and the problems besetting Italy. Her working methods remained the same as those she had developed with Ernest. She was constantly travelling, long car journeys usually driven by Sorino, crisscrossing the peninsula inspecting nurseries, organizing training courses, and visiting neglected orphanages in an attempt to introduce more progressive methods of child care. The conditions in some of these establishments, both State and Church controlled, were reminiscent of those the world later came to see in Ceausescu’s Romania. And at home there was always a steady stream of visitors to her door: teachers, priests and politicians came to her for advice and support. There is no record of her feelings during this period after Ernest’s death but she was now alone and had to continue with ‘The Work’ without her main collaborator.

It was seven years since the end of the war but even in Ortona living conditions remained harsh. The electricity supply was unreliable and water was only available for a few hours a day. The summers were stiflingly hot and winters bitterly cold. Gianna was very house proud and in the small house on the old gun park she fought a continual battle with damp and the fungus which grew on her freshly painted walls.

Her one escape was Rome where she was guaranteed a hot bath and an injection of culture. She was a keen opera and concert-goer and saw all the latest films. She enjoyed good food and conversation and developed a group of friends in the city, mainly independent, professional women like herself; Louise Wood from the AFSC was one of these. Work would frequently take her to Rome, either to meet visiting dignitaries at the start of their tour of inspection or to meet with government officials. Sometimes she would be driven by Sorino, especially if the car was needed to transport the visitors. Otherwise, and when the pressure of working in Ortona became too much for her, she would take the Friday ‘Rapido’ from Pescara and escape to Rome.

Her base in the city was the Hotel Dinesen in Via Porta Pinciana, close to the fashionable Via Veneto and the Borghese Gardens. The hotel no longer exists but in the 1950s it was small, privately owned, with an eccentric clientele. “Each room had its own distinct personality and its own distinct malfunctions… each season had its regular residents who gave eager briefings on the in-house gossip. A few were, or would be, fairly well known literary figures. One spent his winters in Rome because he loved horse races, especially betting on them. There were academics on sabbatical and Swedish opera buffs and middle aged art students, living the bohemian dream of a lifetime in comfort. Usually there was a solitary woman busy about mild self-mythology. One year it was and English woman with an odd accent who claimed she was related to much of the nobility…..Another it.was a middle aged American of the sculptured hair and annealed make up school who babbled to anyone she could trap about her glamorous nights at the opera, nightclubs and restaurants with her ‘young Italian beau,’ a man famous along the Via Veneto as an expensive gigolo.” (AC)

In June 1954 Ann Cornelisen was also staying at the Dinesen. She was 27 years old and the daughter of a wealthy Chicago family. She had a conventional upper middle class upbringing and the family divided their time between homes in Maine and Chicago. In 1944 she was a Chicago debutante and studied at Vassar College from 1944-1946. In February 1953 she married Gordon Carpenter O’Hara but after less than a year the marriage ended in divorce. She left the USA for Europe and in April 1954, arrived in Florence to learn Italian. In June she moved to Rome with the intention of enrolling at the university to study architecture. Unfortunately the university was closed until November and Ann was stuck in an old fashioned hotel with no contacts other than a randy priest who invited her on a motorcycle tour of the country. She declined this invitation and mouldered in her room for a week until eventually she reluctantly accepted an invitation from an acquaintance of her mother to go for drinks to meet an English social worker. She expected to meet a frumpy middle aged woman but instead she met Gianna Thompson, a chic “easily amused woman in her early 30s…..when she talked about Italy, particularly Southern Italy, her eyes glowed with a mystic, almost fanatic passion. They soon realized that they were staying in the same hotel and that evening they had dinner together. “Gianna’s composure I found daunting. Everything about her was so completely, effortlessly in order. She asked me questions about myself… (and)… listened to my answers. Questions about herself she answered in such a way that the next logical question might possibly be an intrusion and so was not asked. About everything else she talked easily (AC).During the day Gianna was busy with a constant round of meetings but the following evening Ann accompanied her to Largo Argentina where they fed the stray cats. Gianna could never resist helping or taking in animals. She had a remarkable ability to heal and calm even the most distressed creature. The following day the two women met again, as if by chance, in the Piazza di Spagna. Gianna suggested they have tea at Babington’s English Tea Room and it was there that she invited Ann to visit Ortona.

It is possible that Gianna engineered the ‘accidental’ meeting in the Piazza di Spagna. She had been a widow for less than two years. Busy as she was and surrounded by people, there was nobody in whom she could truly confide. Ida and Sorino were loyal and devoted but they were employees. Her role as the head of one of the major agencies working in the region meant that she was obliged to keep her distance. Still grieving Ernest, she needed someone to confide in: to gossip to about the work; to moan about the Fund, administrators and bureaucratic do-gooders; someone with whom to share the constant strain of dealing with poverty. She was very lonely.

Gianna and Ann had much in common. Only about five years separated them in age; they both came from privileged backgrounds; both were recently widowed or divorced; and both were only children with dominant mothers. Ann remained a dutiful daughter, constantly reassuring her parents in the USA that she was safe and happy in Italy. Gianna’s relationship with her mother in England was more difficult. Lilian Guzzeloni was born in 1879 (UK Births, Marriages and deaths) and was in her mid 40s when Gianna was born. She was in her mid to late 50s when her husband died and she and Gianna were forced to leave Italy and this may account for her over protective attitude towards her only child. On her visits to London on SCF business, Gianna frequently avoided going to Lincoln to visit her mother and was later to write about the suffocating effect her mother had on her.

Uncharacteristically for one who rarely took impulsive decisions, Ann accepted the invitation to visit Abruzzo “without the faintest idea where it was, what it was, or quite how to spell it”. She writes at length about the culture shock of that first trip to Ortona: the attitudes to women of the Southern Italian male; the destruction still evident from the war; the lassitude of the people; and the appalling living conditions. Perhaps Gianna had deliberately organised this crash familiarisation course and soon Ann was helping out translating sponsorship letters in the office, feeding children in the nursery, and sorting bales of donated clothing in the autopark storage depot. Week by week her stay was extended. She accompanied Gianna on trips to the mountain villages and began to make herself useful as a second pair of eyes on inspection visits.

Gianna drove herself very hard and expected an equal commitment from those around her but in the evenings the two women had time to talk over dinner, usually prepared by Ida. The Save the Children Fund budget may not have been very high but it did provide for the services of a cook/housekeeper and a chauffeur (Sorino). Despite a life lived among some of the poorest people in Europe, Gianna always retained a slight aura of upper class privilege. Ann, the Vassar educated Chicago debutante, would have fitted in very easily and these evenings at dinner under the grape arbour, with the help of a little wine, saw the two women slowly begin to learn about each other’s lives. ‘By the time my few days in Ortona had stretched to a few weeks, I knew a great deal about the facts of Gianna’s life, less about her doubts and disappointments, and nothing about her husband. Her references to him were rare and factual…..I never heard her pronounce the name of this man she had loved. He was always “my husband”, as though, unnamed, he were a figure of fable’. It was several months before she told Ann the whole story of Ernest’s life and the accident that caused his death.

In her book, Ann describes how, in 1954, people paid for their children’s nursery care and how aid was distributed. “Places in the Ortona nursery and the Baby Hut were assigned strictly according to need. For those who were accepted, all food and clothing needed at the centres, including shoes, would be supplied. In return, the mothers were expected to do the cleaning and the laundry…… Clothing was given out on just such as strict a basis. It was earned. Women who signed up to work three afternoons in the sewing room, where all manner of linen for the boys’ home, the hospital, even the nursery were made, qualified for an overcoat or dresses for themselves, or children’s clothing, or a complete, new layette. Men, who signed up to work three days a week on various projects that Sorino supervised, had their choice of an overcoat, a suit, or new heavy duty shoes.” Ann could have been describing Ernest Thompson’s working methods which he outlined in his 1949 report to AFSC.

During the summer of 1954 dates for Ann’s return to Rome came and went as she became increasingly involved in ‘The Work’. She learned how Gianna encouraged nursery teachers to make stimulating toys and play equipment. There was no money so everything had to be recycled or remodelled. The Ortona nursery set the standard for all other nurseries in the region and here, Gianna’s artistic and design skills came to the fore. Sorino was as inventive at acquiring raw materials for toys as he was at acquiring spare parts of the Fund’s aged vehicles and he would spend hours making trains, cars, mobiles, dolls houses etc which Gianna would then meticulously paint. Ann became a toy painter. She was also useful as a driver and was instructed by Sorino on the idiosyncrasies of the SCF vehicles, some of which had been cobbled together from several different models.

She was becoming part of the team and, at the end of October, was left in charge while Gianna was away on a course in Bologna. Her absence coincided with All Souls’ Day. For the last two years she had always contrived to be away from Ortona at this time of the year when families honoured their dead. Ann was summoned to the cemetery at Ortona for a clandestine meeting with Sorino and Pasquale, Gianna’s gardener. In the two years since his death Gianna had never visited Ernest’s grave but, unbeknown to her, Sorino and Pasquale had maintained it, decorating it with flowers at their own expense. Every year on All Souls’ Eve, in accordance with local custom, in front of the grave they set out a table with linen, plates and food. This was to welcome the soul, to assure him he was cared for and expected. On All Souls’ Day itself, Sorino and Pasquale took turns standing by the grave, talking to people who stopped, giving each a card.... with a photograph of Ernest Thompson (with) dates of his birth and death. However, people had commented that the headstone lacked the customary medallion bearing the deceased’s photograph and this year they wanted Ann’s permission to attach one to the headstone. They knew that Gianna would disapprove, that what they were doing was an invasion of her privacy, but local custom was very strong……We all stared at the ground until Sorino asked very quietly that I not tell Gianna. She need never know. I promised I would tell her nothing. Of that he could be very sure.

Gianna returned home and Ann was true to her word. A few days later, she announced that she wanted to stay in Abruzzo.

Click here to go to next chapter

It was seven years since the end of the war but even in Ortona living conditions remained harsh. The electricity supply was unreliable and water was only available for a few hours a day. The summers were stiflingly hot and winters bitterly cold. Gianna was very house proud and in the small house on the old gun park she fought a continual battle with damp and the fungus which grew on her freshly painted walls.

Her one escape was Rome where she was guaranteed a hot bath and an injection of culture. She was a keen opera and concert-goer and saw all the latest films. She enjoyed good food and conversation and developed a group of friends in the city, mainly independent, professional women like herself; Louise Wood from the AFSC was one of these. Work would frequently take her to Rome, either to meet visiting dignitaries at the start of their tour of inspection or to meet with government officials. Sometimes she would be driven by Sorino, especially if the car was needed to transport the visitors. Otherwise, and when the pressure of working in Ortona became too much for her, she would take the Friday ‘Rapido’ from Pescara and escape to Rome.

Her base in the city was the Hotel Dinesen in Via Porta Pinciana, close to the fashionable Via Veneto and the Borghese Gardens. The hotel no longer exists but in the 1950s it was small, privately owned, with an eccentric clientele. “Each room had its own distinct personality and its own distinct malfunctions… each season had its regular residents who gave eager briefings on the in-house gossip. A few were, or would be, fairly well known literary figures. One spent his winters in Rome because he loved horse races, especially betting on them. There were academics on sabbatical and Swedish opera buffs and middle aged art students, living the bohemian dream of a lifetime in comfort. Usually there was a solitary woman busy about mild self-mythology. One year it was and English woman with an odd accent who claimed she was related to much of the nobility…..Another it.was a middle aged American of the sculptured hair and annealed make up school who babbled to anyone she could trap about her glamorous nights at the opera, nightclubs and restaurants with her ‘young Italian beau,’ a man famous along the Via Veneto as an expensive gigolo.” (AC)

In June 1954 Ann Cornelisen was also staying at the Dinesen. She was 27 years old and the daughter of a wealthy Chicago family. She had a conventional upper middle class upbringing and the family divided their time between homes in Maine and Chicago. In 1944 she was a Chicago debutante and studied at Vassar College from 1944-1946. In February 1953 she married Gordon Carpenter O’Hara but after less than a year the marriage ended in divorce. She left the USA for Europe and in April 1954, arrived in Florence to learn Italian. In June she moved to Rome with the intention of enrolling at the university to study architecture. Unfortunately the university was closed until November and Ann was stuck in an old fashioned hotel with no contacts other than a randy priest who invited her on a motorcycle tour of the country. She declined this invitation and mouldered in her room for a week until eventually she reluctantly accepted an invitation from an acquaintance of her mother to go for drinks to meet an English social worker. She expected to meet a frumpy middle aged woman but instead she met Gianna Thompson, a chic “easily amused woman in her early 30s…..when she talked about Italy, particularly Southern Italy, her eyes glowed with a mystic, almost fanatic passion. They soon realized that they were staying in the same hotel and that evening they had dinner together. “Gianna’s composure I found daunting. Everything about her was so completely, effortlessly in order. She asked me questions about myself… (and)… listened to my answers. Questions about herself she answered in such a way that the next logical question might possibly be an intrusion and so was not asked. About everything else she talked easily (AC).During the day Gianna was busy with a constant round of meetings but the following evening Ann accompanied her to Largo Argentina where they fed the stray cats. Gianna could never resist helping or taking in animals. She had a remarkable ability to heal and calm even the most distressed creature. The following day the two women met again, as if by chance, in the Piazza di Spagna. Gianna suggested they have tea at Babington’s English Tea Room and it was there that she invited Ann to visit Ortona.

It is possible that Gianna engineered the ‘accidental’ meeting in the Piazza di Spagna. She had been a widow for less than two years. Busy as she was and surrounded by people, there was nobody in whom she could truly confide. Ida and Sorino were loyal and devoted but they were employees. Her role as the head of one of the major agencies working in the region meant that she was obliged to keep her distance. Still grieving Ernest, she needed someone to confide in: to gossip to about the work; to moan about the Fund, administrators and bureaucratic do-gooders; someone with whom to share the constant strain of dealing with poverty. She was very lonely.

Gianna and Ann had much in common. Only about five years separated them in age; they both came from privileged backgrounds; both were recently widowed or divorced; and both were only children with dominant mothers. Ann remained a dutiful daughter, constantly reassuring her parents in the USA that she was safe and happy in Italy. Gianna’s relationship with her mother in England was more difficult. Lilian Guzzeloni was born in 1879 (UK Births, Marriages and deaths) and was in her mid 40s when Gianna was born. She was in her mid to late 50s when her husband died and she and Gianna were forced to leave Italy and this may account for her over protective attitude towards her only child. On her visits to London on SCF business, Gianna frequently avoided going to Lincoln to visit her mother and was later to write about the suffocating effect her mother had on her.

Uncharacteristically for one who rarely took impulsive decisions, Ann accepted the invitation to visit Abruzzo “without the faintest idea where it was, what it was, or quite how to spell it”. She writes at length about the culture shock of that first trip to Ortona: the attitudes to women of the Southern Italian male; the destruction still evident from the war; the lassitude of the people; and the appalling living conditions. Perhaps Gianna had deliberately organised this crash familiarisation course and soon Ann was helping out translating sponsorship letters in the office, feeding children in the nursery, and sorting bales of donated clothing in the autopark storage depot. Week by week her stay was extended. She accompanied Gianna on trips to the mountain villages and began to make herself useful as a second pair of eyes on inspection visits.

Gianna drove herself very hard and expected an equal commitment from those around her but in the evenings the two women had time to talk over dinner, usually prepared by Ida. The Save the Children Fund budget may not have been very high but it did provide for the services of a cook/housekeeper and a chauffeur (Sorino). Despite a life lived among some of the poorest people in Europe, Gianna always retained a slight aura of upper class privilege. Ann, the Vassar educated Chicago debutante, would have fitted in very easily and these evenings at dinner under the grape arbour, with the help of a little wine, saw the two women slowly begin to learn about each other’s lives. ‘By the time my few days in Ortona had stretched to a few weeks, I knew a great deal about the facts of Gianna’s life, less about her doubts and disappointments, and nothing about her husband. Her references to him were rare and factual…..I never heard her pronounce the name of this man she had loved. He was always “my husband”, as though, unnamed, he were a figure of fable’. It was several months before she told Ann the whole story of Ernest’s life and the accident that caused his death.

In her book, Ann describes how, in 1954, people paid for their children’s nursery care and how aid was distributed. “Places in the Ortona nursery and the Baby Hut were assigned strictly according to need. For those who were accepted, all food and clothing needed at the centres, including shoes, would be supplied. In return, the mothers were expected to do the cleaning and the laundry…… Clothing was given out on just such as strict a basis. It was earned. Women who signed up to work three afternoons in the sewing room, where all manner of linen for the boys’ home, the hospital, even the nursery were made, qualified for an overcoat or dresses for themselves, or children’s clothing, or a complete, new layette. Men, who signed up to work three days a week on various projects that Sorino supervised, had their choice of an overcoat, a suit, or new heavy duty shoes.” Ann could have been describing Ernest Thompson’s working methods which he outlined in his 1949 report to AFSC.

During the summer of 1954 dates for Ann’s return to Rome came and went as she became increasingly involved in ‘The Work’. She learned how Gianna encouraged nursery teachers to make stimulating toys and play equipment. There was no money so everything had to be recycled or remodelled. The Ortona nursery set the standard for all other nurseries in the region and here, Gianna’s artistic and design skills came to the fore. Sorino was as inventive at acquiring raw materials for toys as he was at acquiring spare parts of the Fund’s aged vehicles and he would spend hours making trains, cars, mobiles, dolls houses etc which Gianna would then meticulously paint. Ann became a toy painter. She was also useful as a driver and was instructed by Sorino on the idiosyncrasies of the SCF vehicles, some of which had been cobbled together from several different models.

She was becoming part of the team and, at the end of October, was left in charge while Gianna was away on a course in Bologna. Her absence coincided with All Souls’ Day. For the last two years she had always contrived to be away from Ortona at this time of the year when families honoured their dead. Ann was summoned to the cemetery at Ortona for a clandestine meeting with Sorino and Pasquale, Gianna’s gardener. In the two years since his death Gianna had never visited Ernest’s grave but, unbeknown to her, Sorino and Pasquale had maintained it, decorating it with flowers at their own expense. Every year on All Souls’ Eve, in accordance with local custom, in front of the grave they set out a table with linen, plates and food. This was to welcome the soul, to assure him he was cared for and expected. On All Souls’ Day itself, Sorino and Pasquale took turns standing by the grave, talking to people who stopped, giving each a card.... with a photograph of Ernest Thompson (with) dates of his birth and death. However, people had commented that the headstone lacked the customary medallion bearing the deceased’s photograph and this year they wanted Ann’s permission to attach one to the headstone. They knew that Gianna would disapprove, that what they were doing was an invasion of her privacy, but local custom was very strong……We all stared at the ground until Sorino asked very quietly that I not tell Gianna. She need never know. I promised I would tell her nothing. Of that he could be very sure.

Gianna returned home and Ann was true to her word. A few days later, she announced that she wanted to stay in Abruzzo.

Click here to go to next chapter